How Your Car Stops: The Science of Friction

It’s a moment we take for granted: pressing the brake pedal and feeling your car smoothly, reliably slow to a halt. This essential function is enabled by a surprisingly simple principle: friction. But what exactly harnesses this power to stop a multi-ton vehicle? The answer lies in the brake lining.

Anatomy of a Stop: Drums and Discs

Braking systems in modern vehicles generally come in two main forms: disc brakes and drum brakes. While they operate differently, both rely on a friction material to do the heavy lifting of converting kinetic energy (motion) into thermal energy (heat), which is then dissipated into the air.

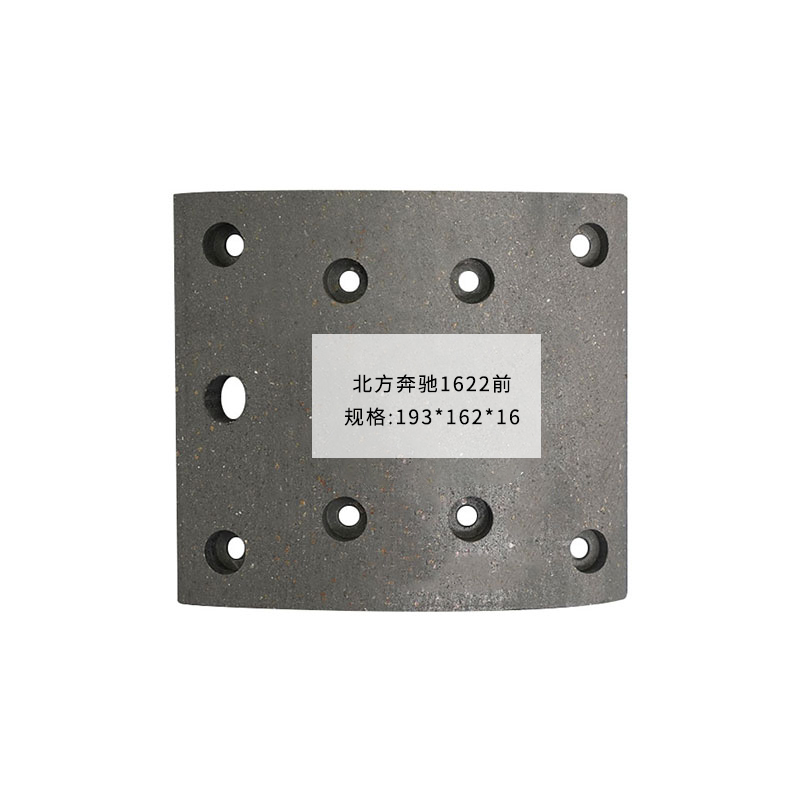

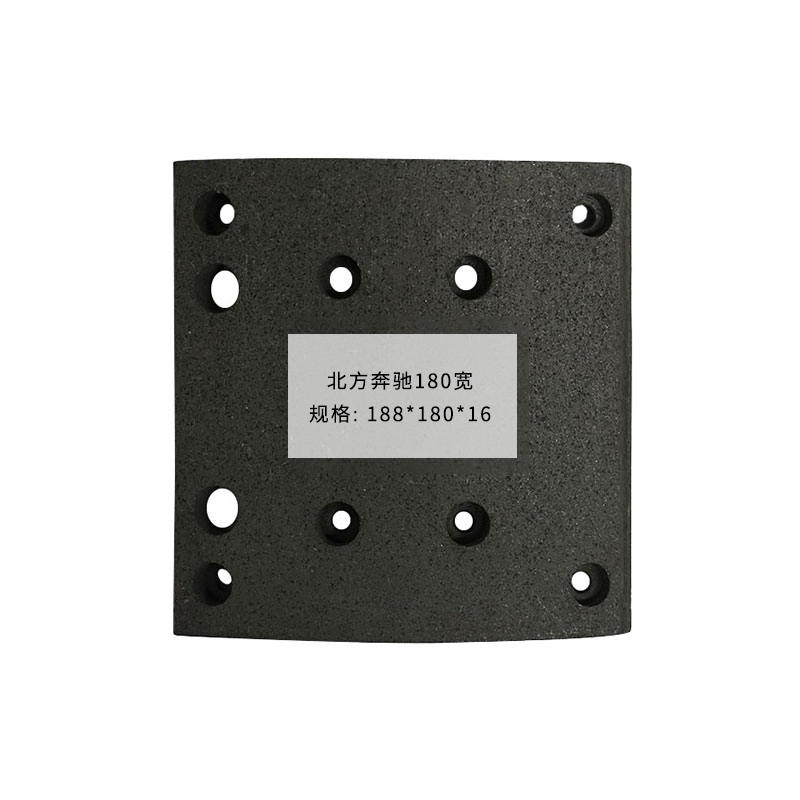

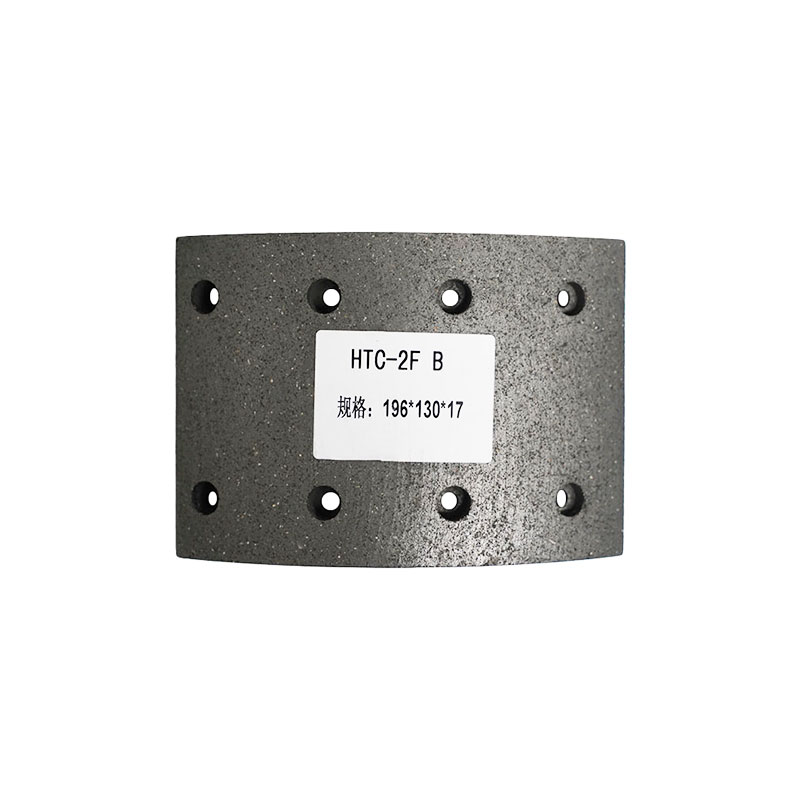

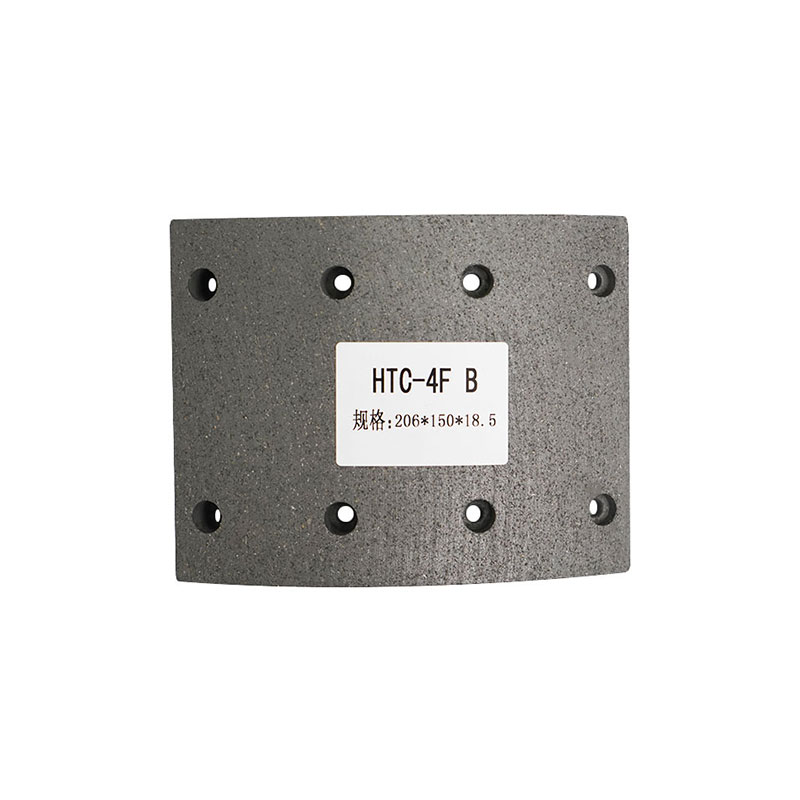

Drum Brakes and the Brake Lining

In drum brakes, the brake lining is a semi-circular piece of friction material bonded or riveted to a brake shoe. When you step on the brake pedal, the shoe is forced outward, pressing the brake lining against the inside surface of a rotating brake drum. The resulting friction slows the wheel.

Disc Brakes and Brake Pads

In disc brake systems, the friction material is packaged as a brake pad. A brake pad is essentially a small, thick block of friction material—which is the equivalent of the brake lining in this context—attached to a rigid metal backing plate. When the brakes are applied, a caliper squeezes these pads onto a spinning rotor (a metal disc) from both sides, creating the necessary friction to stop the wheel. Disc brakes are generally more efficient at dissipating heat and are common on the front wheels of almost all modern cars.

What the Brake Lining Is Made Of: A Material Evolution

The performance and durability of your brakes are entirely dependent on the composition of the brake lining. Historically, asbestos was a common material due to its heat resistance and durability. However, because of its severe health risks, it has been largely phased out and replaced by safer alternatives.

The Three Main Formulas

Today’s friction materials generally fall into three categories:

- Non-Asbestos Organic (NAO): These linings are made from a mix of fibers (like glass, carbon, or rubber) and resins. They are generally quieter and softer on the rotor, making them ideal for standard commuter driving. They tend to wear out faster and are not suited for high-performance applications.

- Semi-Metallic: Containing 30–65% metal (such as iron, copper, or steel wool), these linings offer superior braking performance, better heat transfer, and longer life than NAO pads. They are, however, often noisier and can be harder on the rotors.

- Ceramic: Made from dense ceramic fibers mixed with copper fibers and other fillers, ceramic brake lining offers excellent braking power, very low dust, and exceptional quietness. They are more expensive but are often considered the premium choice for street driving due to their performance and clean operation.

The Wear and Tear Factor

The very process that stops your car—friction—is also what slowly destroys the brake lining. Every time you brake, a small amount of the lining material wears away as heat is generated. This is why brakes need to be inspected and replaced periodically. A worn brake lining can lead to metal-on-metal contact, which severely damages the drums or rotors, dramatically reduces stopping power, and creates a high-pitched squealing sound—nature’s way of telling you it’s time for a brake job. Monitoring the thickness of your brake pads or linings is a critical part of vehicle maintenance to ensure safety.

English

English 中文简体

中文简体